Many people, of which I am one, consider Polynesians to be the greatest navigators in history. When Greeks and Romans were merely plying the Mediterraean Sea using a few rudimentary directional tools, Polynesians navigated long distances over open ocean without instruments, by using wayfinding techniques that included stargazing and other observations.

In simple terms, wayfinding is the process of maintaining a course to a destination. A pet cat uses wayfinding to return home each day. Birds migrate long distances to the same breeding grounds every summer. Hawaiian humpbacks swim between Hawaiʻi and Alaska each year. Without using a map, signage, or GPS, you can likely find your way to many familiar places.

In stark contrast to other navigators of their time, Polynesians used a combination of wayfinding techniques, including the sun, the moon, detailed knowledge of the stars and planets, direction of ocean swells, cloud formations, bird flight, and other clues.

Vikings were also exceptional wayfinders. Archaeological evidence indicates that Vikings sailed in northern latitudes during long summer days using a sun compass to gauge latitude that helped them chart a course. This technique allowed them to venture farther from shore, but more importantly, to find their way back home.

Many other seafaring cultures explored only the coastal regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Until the sextant came into use in the 18th Century, sailors traveled primarily by day using a compass and hourglass. They also depended on coastal landmarks, the sun, and to a limited extent, some stars at night.

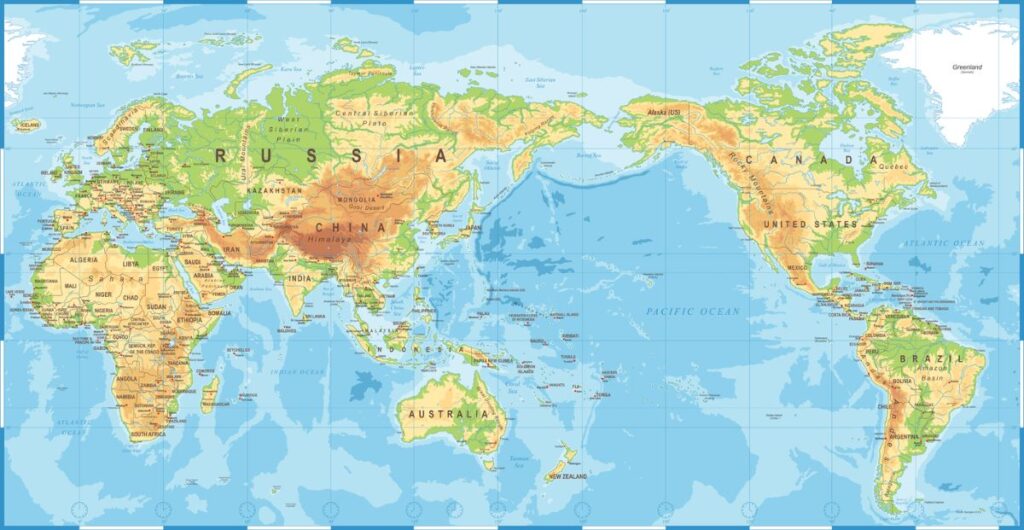

Polynesians navigated the vast Pacific in double-hulled canoes discovering hundreds of islands, from Tonga and Samoa in the Western Pacific, to Easter Island in the East, and the Hawaiian Islands in the North. Often referred to as The Polynesian Triangle, this vast area covers nearly one million miles of open ocean. It was an astonishing feat, unprecedented to this day.

World map illustration by dikobraziy via iStock by Getty Images

Wayfinding techniques

Day or night, there are many directional cues used by experienced Polynesian navigators to find their way across the open ocean. These cues include the sun, moon, stars, planets, ocean swells, wind, cloud formations, and seamarks.

The sun is the primary guide in Polynesian wayfinding. Each day, the navigator aligns the rising and setting sun with marks on the canoe railing. This mark is paired with a single point at the stern to give a bearing that corresponds to directionals on the Hawaiian star compass.

The rising and setting points of the moon, stars, and planets each day, the alignment of the crescent moon, and the moon’s position relative to stars and planets are additional directional cues.

Ocean swells travel from one point on the horizon to a point directly opposite on the horizon (180 degrees), passing under the canoe. On the darkest nights under complete cloud cover, the wayfinder can depend on his or her detailed knowledge of the ocean by feeling the swell patterns. These patterns help to determine direction. When sensing a change in pattern they can also indicate small islands that are not visible on the horizon.

Wind direction can also be used to hold a course. However, if the wind changes direction, it must be checked against other navigational clues, including ocean swells, as well as the direction of the rising and setting of the sun, moon, stars, and planets.

Seamarks work much like landmarks on coastal voyages. Seamarks in mid-ocean can include swarms of fish, flocks of birds, drifting wood or vegetation, distinctive swells or cloud formations, and other observations along a route. Seamarks were given a name and significance, such as “a day’s sail downwind of land”. Such clues were passed down from one generation to the next.

Signs of land can include drifting vegetation or seabirds. Clouds pile up over islands that are not yet visible in the distance. In addition, landmass can be reflected in the sunlight or moonlight.

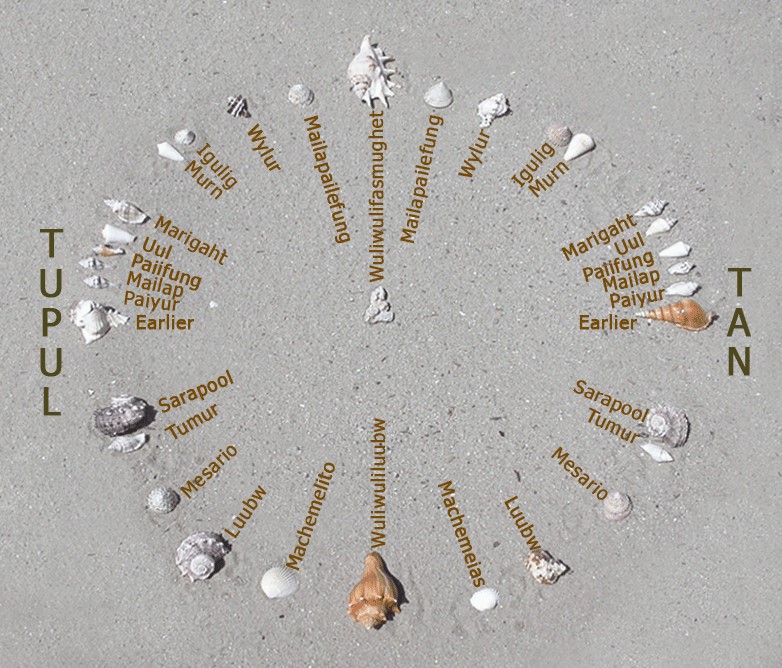

A photograph of a recreation of Mau Piailug’s (1932-2010) star compass–shells on sand with Satawalese labels–as described by the Polynesian Voyaging Society. Photo by Newportm. (CC3)

Hawaiian Star Compass

Since Polynesian navigators passed their knowledge verbally, much of the knowledge about wayfinding was eventually lost. Today, the Polynesian Voyaging Society is reclaiming some of this information, organized into the Hawaiian star compass—a series of stargazing charts.

Polynesians did not use any physical device such as the magnetic compass or nautical chart. Rather, these intrepid sailors were experts at stargazing. They memorized the rising and setting positions of hundreds of stars.

These rising and setting points—or star lines—become useful clues for the navigator. Stars travel in a straight line across the sky from east to west. A star that rises on a point in the NE horizon sets in the NW horizon. A star that rises in the SE sets in the SW. Along with wayfinding clues, Polynesians were able to traverse the vast Pacific Ocean and discover hundreds of islands.

Developed by Native Hawaiian Pwo (Master) Navigator Nainoa Thompson, the star compass is a useful way to memorize the sky. The Hawaiian star compass describes in ʻolelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) all the major stars and star groups (constellations).

Nainoa Thompson’s Hawaiian Star Compass with the Brightest Stars (PDF)

The Hawaiian star compass is composed of 32 equally spaced points around the 360° horizon, divided into quadrants:

- Ko’olau (NE quadrant or windward direction)

- Malanai (SE quadrant)

- Kona (SW quadrant or leeward direction)

- Ho’olua (NW quadrant)

Each quadrant in the star compass describes the Eastern sky in a different season of the year and is defined by a star line.

The four cardinal directions in the star compass also have traditional Hawaiian names:

- Hikina (arriving or coming), where the sun and stars “arrive” at the (eastern) horizon

- Komohana (entering), where the sun and stars “enter” into the (western) horizon

- ‘Akau (right, i.e. north when facing west, the direction of the sun’s course)

- Hema (left, meaning south)

Hawaiian Star Lines

The Hawaiian navigator memorizes each star line in the compass. He or she can then imagine the entire 360° celestial sphere—even on a cloudy night when only part of the sky is visible—and therefore maintain direction.

The four star-lines follow each other in the sky. In order from winter to fall, they are:

- Ke Ka o Makali‘i (“Canoe-Bailer of Makali‘i”) is visible winter to spring. It rises in the east like a cup, holding the constellation of Orion and Taurus. It sets in the west, pouring the content of the cup on the western horizon.

- Iwikuamo‘o (“Backbone”) is visible spring to summer. It runs from Hoku-pa’a (the North Star) to Hanai-a-ka-malama (the Southern Cross). Two stars in Na Hiku (Big Dipper) point to Hokupa‘a.

- Manaiakalani (“Chief’s Fishline”) is visible summer to fall. It is dominated by The Huinakolu (Navigator’s Triangle) in the northern sky and Ka Makau Nui o Māui (Scorpio) in the southern sky.

- Ka Lupe o Kawelo (“Kite of Kawelo”) is visible fall to winter. It is made up of the Great Square of Pegasus. The four stars of the Great Square are named for Hawaiian chiefs; Keawe of Hawaiʻi Island, Piʻilani of Maui, Kākuhihewa of Oʻahu, and Manokalanipo of Kauaʻi.

Hanaiakamalama (Crux, aka Southern Cross) in the starry background of the Milky Way from Mapleton National Park, Queensland 2019 image by Yulanlu97 (CC4) via Wikimedia Commons

Hanaiakamalama (Crux) is a constellation of the southern sky that includes four main stars in a cross-shape, commonly known as the Southern Cross. It is a sigificant constellation in Polynesian wayfinding. (Hanaiakamalama is also the name of a Hawaiian goddess and Queen Emma’s residence (now a museum) in Nuʻu-anu Valley on the island of Oʻahu.)

At the South Pole, the two stars pointing north to south in the Southern Cross are directly overhead. As you travel north, the distance from the top or northern star, Gacrux (Gamma Crucis), to the bottom or southern star, Acrux (Alpha Crucis), is eventually the same distance from the bottom star to the horizon. This phenomenon occurs only in the latitude of Hawai’i.

In the Hawaiian sky, Crux appears for several weeks in late December and January. Find it in the southern sky just above the horizon before sunrise.

You might also like: When and where to watch whales for free in Hawaiʻi (hawaiionthecheap.com)

Mahina as Compass

Like many cultures around the world, the traditional Hawaiian calendar was based on the phases of mahina (the moon). The year had twelve months of 29.5 moon phases. (Every three to six years, a thirteenth lunar month was added—similar to Leap Year in todayʻs Gregorian solar calendar.)

Each month started with Hilo* (the new moon) and ended with Mauli or Muku (the dark moon). The passage of days were marked by three 9- or 10-day phases of the moon:

- Ho‘onui (growing bigger, i.e. wasing moon) beginning on the first crescent.

- Poepoe (round or full) as the moon became full and round. The moon appears full on three days, the 14th (Akua), the 15th (Hoku), and the 16th day (Māhealani).

- Emi (decreasing, i.e. waning) as the moon loses its light. The last quarter moon rises around midnight and sets around noon. Muku, the new moon, is unseen between the earth and the sun.

* Hilo was a famous Hawaiian navigator. As with most words in ʻolelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language), Hilo has more than one meaning: to “braid” or “twist” (used in rope making) and “first night of the new moon”. Hilo is also a type of grass, a variety of sweet potato, and a city on the Big Island of Hawai’i.

When a crescent moon is high in the sky, you can find your direction by drawing a line connecting the sharp points on the crescent and continuing straight to the horizon to find South. (If you are in the Southern hemisphere then it points to North.)

In addition to navigational uses, the phases of the moon were used to determine other aspects of daily life (then and now), such as optimal conditions for coastal versus deep sea fishing, favorable times to plant crops, the presence of Box Jellyfish and Portuguese Man-of-War, and other aspects of daily life (even the best day to marry).

Hawaiian Star Chart

ʻImiloa Astronomy Center (imiloahawaii.org) is a multi-service organization of the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo. They share Polynesian navigation history and stargazing knowledge. Each month, ʻImiloa provides the current star chart in the Hawaiian Star Compass.

Find the current Hawaiian Star Chart online at Skywatch — ʻImiloa Astronomy Center

You might also like:

- Oʻahu: public stargazing events around the island (hawaiionthecheap.com)

- Polynesian Discoverers’ Day in the Hawaiian Islands (2nd Monday in October) (hawaiionthecheap.com)

Event calendar of free and affordable things to do

Listed below are all types of free and affordable things to do in the next 30 days across the Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina.

Featured Events are listed first each day, highlighted by a photo. These are unique, popular, or annual events that we or our advertisers don’t want you to overlook.

You might also like: Hawaiʻi on the Cheap – affordable living and things to do (hawaiionthecheap.com)